The Crypto Travel Rule: Challenges and Solutions

by Malcolm Wright, Co-Chair — AML | KYC | CTF Working Group, Global Digital Finance

I have just returned from the V20 in Osaka where some of the largest virtual asset service providers, regulators, and legislators met to forge a way forwards on how to implement the ‘travel rule’ that was ratified by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on 21 June 2019.

Over the course of two days, the FATF through the outstanding Tom Neylan provided supportive input and strong guidance on the expectation for the industry. Meanwhile, workshops provided the forum through which the industry could discuss thoughts towards solutions. Although no white smoke was seen at the end of the two days, the industry agreed in principle that a not-for-profit body was required to oversee the governance and delivery of a global solution; a first step then.

Sian Jones of Founder of COINsult and Senior Advisor on DLT to the Gibraltar Financial Services Commission also provided invaluable input drawn on her extensive experience with regards to how solution designers need to approach the creation of any system. Any solution should:

- Include all VASPs, everywhere

- Include all virtual assets, present and future

- Handle tens of millions of transactions a day

- Be scalable

- Be reliable, all the time

- Be available, all the time

- Be maintainable

But equally important, any solution must also:

- Be acceptable to industry, governments, and supervisors

- Be inclusive of financial institutions and others

- Implement global and national requirements

- Respond rapidly to changes

- Be well-resourced

I have added to this with my own list of four guiding principles:

1. Any solution should minimise regulatory impact

- Where solutions require regulatory change, barriers to adoption are created. Regulatory change takes time — a lot of time — so the less regulatory change required to accommodate any solution, the better.

- Data privacy, data sharing, and data security need to be respected on a jurisdictional basis. This should be regarded as a red line.

2. Any solution should be globally available

- Solution fragmentation will increase implementation costs and complexity, as well as increasing margins for error and omission

- To prevent solution fragmentation, the industry must adopt a common, global standard

3. Any solution should minimise implementation cost

- Solutions will require both network infrastructure and firm-level integration

- High cost to implementation will harm smaller firms and risk innovation

4. Any solution should be open source / not-for-profit

- Solutions should not benefit a party for financial gain

Over the past couple of months, I’ve heard many providers offering solutions to the travel rule. Whilst innovation is necessary, in some respects it should also be tempered. A next-generation KYC solution may be great in principle, but if it takes 5 years to adopt globally then it is not fit for purpose — for today, at least. Additionally, regulators need to be comfortable with any solution and the closer to something that resembles familiarity, the better. That’s not to say that ‘under the hood’ things are innovative. But there is a danger of over-engineering innovation to the detriment of effectiveness goals.

We should also remember why the rule is here in the first place; to prevent terrorists and criminals from having unfettered access to the financial system. To do this, the travel rule has two objectives:

- To make every reasonable effort to prevent funds being sent to a sanctioned entity. It is primarily the responsibility of the sending VASP to manage this through screening the name of the beneficiary against appropriate sanctions lists, although the receiving VASP should also screen the originator to close the loop as a means of best practice.

- To have originator and beneficiary information readily available to law enforcement officers upon appropriate request. Such requests can sometimes be time sensitive. Moreover, there should be no reliance on another party to produce that information; that is, both the sending and receiving VASPs should hold this information independently.

Challenges to Solutions

Some of the solutions I have seen have had considerable technical thought applied by some very smart people. However, I have yet to see something I believe is sufficient to meet the guiding principles. I’m not discounting them completely, but they create significant challenges that require a long time to overcome that would not make them suitable to meet the FATF’s urgent priorities.

- Shared KYC Utilities

A few years back, I was fortunate to be part of the leadership team that built the world’s first shared KYC managed service. I can tell you it is really hard to do.

Some of the challenges for consideration include alignment of KYC policies for every VASP globally, ownership of risk, reliance on third parties, enhanced due diligence, building and managing a global team of trained compliance staff, as well as data privacy and data processing requirements.

Such an approach would require substantial changes to national legislation, some of which would be unlikely to happen such as in countries where data has to be processed and stored in-country. It would also require substantial compliance teams to manage, and large teams of staff means human risk and high run costs; what if the KYC is not completed adequately, or staff are targeted by criminals to hand over private data (yes, this does happen). More so, imagine a single centralised global database of KYC records; a rich treasure trove for hackers both independent and state sponsored.

Three of the four guiding principles (1, 2, and 3) then could not be facilitated under this option.

2. Closed-Loop Wallets

Another idea floated is that of the closed loop wallet. Everyone uses the same wallet when using an exchange, or all exchanges use the same wallet technology. There may be some consideration here for when funds are taken off-exchange, but for the general population the concept of moving your funds out to another device in order to then transfer them onwards adds a layer of complexity and friction that will drive customers away. Some exchanges may also be reticent buying into the idea.

Again, challenges would exist with regards to the cost of such a solution. Then there are political issues; as we have seen with technology manufacturers lately, it is easy for technology to come under scrutiny in one or more countries to the point it is no longer considered viable. Imagine if that happened to a common standard wallet.

At least two of the four guiding principles (2 and 3) could not be facilitated under this option.

3. Zero-Knowledge Proof

According to Wikipedia, Zero-Knowledge Proof (or ZKP) is the concept that one party (the prover) can prove to another party (the verifier) that they know a value x, without conveying any information apart from the fact that they know the value x. To put another way, when onboarding a customer there is no need to see their KYC data; it is already proved through a technical means so all you receive is an identifier that acts as proof.

It sounds like a utopian solution to the travel rule by protecting the need to share data, but it comes with its own challenges. The first being that obliged firms have to store certain documents. This is often mandated by national law. Thus, substantial regulatory change would be required to adopt. Secondly, the technology is new and so not yet tested in the wild to the extent a robust and immediate solution would require. Longer term, perhaps this can be proven out but for right now it would be hard for regulators everywhere to get comfortable with this, particularly if it is applied to the KYC of a sector already considered high-risk.

There is also something I have termed ‘inception point risk’. What happens if the original information when the ZKP record was created is wrong or fraudulent? It means that every use of the ZKP to onboard or in transactions would then potentially be based on false information but where compliance officers would have a false perception that the ZKP offered a security or assurance that the customer was indeed that customer.

Thus, again I believe two of the four guiding principles (1 and 2) are currently missed here.

4. Hashing of Originator / Beneficiary Information

One further concept raised was that of hashing the originator and / or beneficiary information and sending the hash in a cover message instead of the actual data. The beneficiary would provide a ready-made hash of their personal data that has been provided to them by their exchange, and this in turn would be provided to the sending VASP to transmit. The concept though, involves the sending VASP not seeing the beneficiary name and vice versa. Thus, sanctions screening could not take place because neither VASP would see the counterparty’s underlying details. Further, law enforcement could not enquire of either the sending or the beneficiary VASP without relying on the counterparty in order to see both ends of the transaction, meaning the two objectives of the travel rule cannot be met.

The discussion has also been to include information on the blockchain. However, in this situation I would draw you to the excellent document by Hogen Lovells titled A guide to blockchain and data protection in which they state ‘A hash that represents a person’s ID card or medical record would likely be considered personal data even though the hash itself is impossible to reverse engineer into the original personal information’.

Thus, for the time being this solution would not meet two of the four guiding principles (1 and 2).

5. X.509 Certified Addresses

At the FATF Private Sector Consultative Forum in May 2019 in Vienna, a presentation was provided with regards X.509 certificates (the certificates that make https work in your browser). Some challenges were raised that remain valid. The idea was, each public address could be supported by an X.509 certificate that would identify the owner’s name.

Those of you who know about domain names will know that in 2018, the owners of domain names had to be obfuscated because of GDPR. That was actually a major blow to compliance staff who use that information as part of their CDD process. Thus, this is unlikely to be viable from the outset.

Further, concerns have been raised on the ease of X.509 exploits; the Stuxnet malware, and issuing authority hacks (the firms that issue the certificates) that resulted in redirected Internet traffic away from major web sites.

It would also add cost to every address created as a certificate would need to be produced.

Again then, it appears that at least two of the three guiding principles (1, 2 and 3) are missed.

So what is the answer?

If all of the above sounds depressing it need not be. The solution is actually very simple. Bear in mind, at first glance regulators want something that will not appear to be too technically challenging, particularly where the regulator is still coming up to speed with technology.

What I present below is my concept of a solution. It is just 3 steps. I add here that I have no vested commercial interest to the outcome. Simply, I want to see the industry and regulators be able to reach a consensus on a solution that will stop illicit funds being funnelled through virtual asset service providers. I believe this offers simplicity, adheres to the guiding principles including no change to local regulation, follow’s Sian Jones’ input, and minimises data privacy impact.

Step 1: Find the VASPs

The first step of the process is to build a consistent and accurate list of VASPs. Conceptually, creation of a global not-for-profit membership body, potentially based out of Switzerland or Belgium, would offer a platform around which this information could be collated. This body could be restricted in scope to begin with to oversight of the VASP payment transfer mechanism.

With the body in place and VASPs onboarding as members, the VASPs could then register on a domestic basis in each country they have customers. On doing so they would receive a unique identifier similar to a SWIFT code. The databases could be overseen by the membership body. As regulators legislate for the FATF recommendations, the regulators could enhance the data with confirmation of registration or license.

The local databases would then be published to a global list of VASPs (or GLOV). Where local licensing regimes are in place, it may be that only licensed VASPs are published adding an additional layer of compliance or risk mitigation against VASPs with poor controls. Again, the GLOV would be maintained by the membership body.

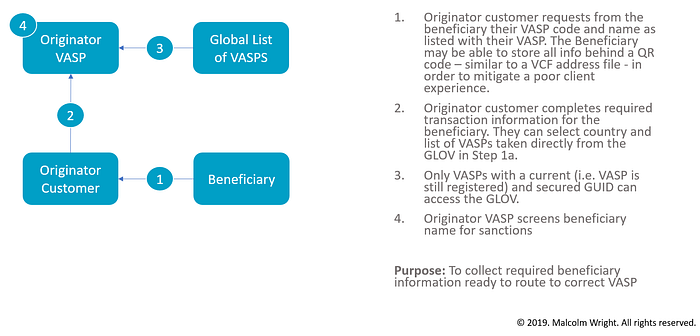

Step 2: Gather the Data

The second step of the process would be to gather the beneficiary data. There is not much to gather here; the beneficiary’s VASP code from the prior step and the beneficiary’s name as listed with the VASP will suffice. The VASP code, if country-specific will additionally aid compliance with cross-border compliance risk mitigation where the VASP code can be cross-referenced against the GLOV to ensure that details are remitted to the correct VASP, and the jurisdiction of the customer is then known.

Of course, in the absence of a VASP code, then the originator could certify the transfer is going to a non-custodial wallet and Step 3 below would then not apply.

Importantly, this step could be completed before the transmission infrastructure is built allowing firms to prepare for implementation of the full travel rule requirements sooner.

Step 3: Remit the Data

In the final stage, the sending VASP screens and then shares the required data with the beneficiary VASP over a secure API (programmatic interface requiring no human intervention). This will be peer-to-peer with no centralised clearing house and the notification will be separate from the underlying asset being transferred.

The beneficiary VASP will then screen required data and can also check for a name match or near-name match in real time. If there are mismatches (i.e. name or wallet address), the API can provide immediate feedback to the sending VASP. This may allow the sending VASP to reject the transaction or, perhaps if data suggests, to raise a suspicious activity request (e.g. if there were a significant number of such failures).

Meanwhile, if the beneficiary VASP received an inbound transaction with no cover instruction from an originator VASP it could take one of two actions depending on the risk of the client; either assign as an inbound transaction from a non-custodial wallet or make enquiries to the beneficiary on the source of funds. For repeated inbound transfers with no cover instruction from a sending VASP, a beneficiary VASP may decide to make further enquiries on the nature of the beneficiary’s business and on the use of their account should the VASP believe it to be suspicious.

Solution Benefits

Of course, this is a high-level overview. There is more detail behind this either built out or that needs to be built out. But, I believe this to be implementable, achievable, and can provide an excellent baseline upon which innovation can then be built out further. With the benefit of a baseline, it then becomes possible to innovate with a metrics-driven approach which for regulators is key; if it is possible to prove that a new innovation is more effective then the likelihood of adoption is higher than attempting innovation with no proven data.

The system also incorporates substantial benefits for law enforcement, also within the parameters of existing legislation but I will save these for a further article.

To summarise the solution benefits then:

Capability for rapid adoption

- Low technical and maintenance overhead

- Minimal / no regulatory change

- Low implementation cost

Capability for effective AML / CFT response

- Allows for country risk assessment on beneficiary transfers

- Effective routing of information to Beneficiary VASPs

- Verification feedback loop from Beneficiary to Sending VASPs to identify information mismatches

What would a roadmap look like?

I see four workstreams that could potentially be delivered inside 12 months;

- Governance — step up the not-for-profit organisation

- Protocols — Ideally separated from the not-for-profit organisation, a set of standards for data, messaging, storage, audit, etc.

- Technology — The actual build itself. Fundamentally, not challenging with the right protocols and approved system design in place. There is very little technical work to this solution.

- Go to Market — How to operationalise the system and move to BAU, including maintenance. This would also need to include significant industry outreach to bring VASPs onboard. The independence of the not-for-profit is key.

Beyond this roadmap there are further phases. As I mentioned earlier, I will talk later about some additional rapid response options that the system could allow for law enforcement as well as a mechanism to resolve the FATF’s note 118 on blacklisting addresses as mentioned in the Guidance for VASPs.

To conclude then there is also an opportunity to innovate. But, that is secondary to ensuring adequate AML and CFT protections and compliance. If we solve the problem and baseline first, the industry can then innovate to improve effectiveness and privacy; there does not need to be a final solution on day one.

==================

The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the author’s employer or associations. The author retains the intellectual property claim on the idea.